By Caroline Chen and Michelle Cortez

Some patients with advanced cancer and their doctors are tentatively whispering a word they hadn’t dared to utter before: “cure.”

Cancer remains a death sentence for millions every year, causing one in every seven deaths around the globe. Over the years the wily disease has outsmarted the medical world’s best attempts to rein it in with an uncanny ability to evolve and mutate, adapting to whatever new drugs are thrown its way. Yet a new degree of optimism is emerging in labs and hospitals around the globe as researchers coax the immune system to hunt down malignant cells or suppress cancer’s defense mechanisms.

“We are in the midst of a huge paradigm shift,” said Padmanee Sharma, professor of genitourinary medical oncology and immunology at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. With the new drugs in advanced melanoma, she says, “about 20 percent are getting long-term survival.”

Many questions remain. Some cancers like pancreatic cancer and brain tumors remain largely untreatable. And, where progress has been made, so far only a small percentage of patients respond to the latest treatments. Still, there is now statistical evidence that some people with tumors who would have previously died within months are living cancer-free for years, raising the tantalizing possibility of developing cures for far more cancers in the future.

“We’re early in the journey,” said David Reese, senior vice president of translational sciences at biotechnology firm Amgen Inc. “Why is it still a minority of patients that have these extraordinary responses? That’s the hard work that needs to be done now.”

Jimmy Carter

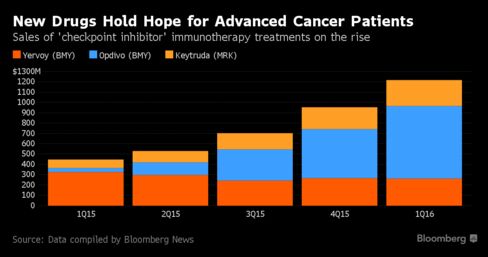

Progress in treating advanced melanoma, one of the deadliest cancers with a median survival rate of less than 9 months, have been especially promising. These drugs include Bristol-Myers Squibb & Co.’s Yervoy and Opdivo as well as Merck & Co.’s Keytruda. At the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in Chicago this week, researchers will present data showing 40 percent of advanced melanoma patients in a trial of Keytruda have been in remission for three years.

In December, former president Jimmy Carter, 91, said scans showed no sign of the advanced melanoma he had been diagnosed with just four months earlier, following treatment with Keytruda. Some of the earliest patients receiving Yervoy have now been alive for more than a decade, double the five-year survival rate that’s deemed a cure.

Stage IV Melanoma

Alan Kravitz, a 74-year-old retired gourmet grocery store owner, was one of the first patients to get Opdivo when he was diagnosed with stage IV melanoma. With his prospects looking grim, Kravitz’s doctor told him to get his affairs in order, then enrolled him into a clinical trial of the Bristol-Myers drug in 2006.

“When someone tells you the average survival from this diagnosis is measured in months, you’ll do whatever you have to do,” Kravitz said from his home in Clinton, Connecticut.

Kravitz received infusions twice a month, and a year later the nodules on his lungs were virtually gone. The mass on his liver, once larger than a golf ball, melted away. All that’s now left is a scar. A decade after his diagnosis, Kravitz takes no medicine and shows no sign of cancer.

“The goal here is to cure people of their cancer so we don’t need continuous therapy,” said his doctor, Mario Sznol, an oncologist and co-director of the skin cancer unit at Yale Cancer Center.

Cancers Unmasked

The new melanoma drugs are called “checkpoint inhibitors” because they unmask cancers by removing the tools malignant cells use to evade the immune system. They’re also being used against some lung cancers, kidney cancer and Hodgkin lymphoma, and being tested in dozens of other tumor types. Yet these drugs are of little use if a patient’s body isn’t producing T-cells, a form of white blood cells, that would recognize, attack and kill malignant cells in the first place.

One method being tested to boost patient’s T-cells is a personalized treatment known as CAR-T, in which doctors genetically engineer each person’s immune system T-cells to target specific tumors. In some blood cancer patients, the treatment has yielded startling improvements in the sickest of patients.

One of those patients is Emily Whitehead, today a healthy, happy fifth-grader. In 2012, then 6-year-old Emily’s acute lymphoblastic leukemia relapsed and her doctors suggested home hospice care, her father recalled.

Instead, Emily’s parents enrolled her in a clinical trial, where she became the first child to ever receive CAR-T therapy. It did not go well. She reacted to the treatment with a 105 degree fever and hallucinations. She remained in a coma for two weeks, breathing through a ventilator.

Symptom Free

Yet the treatment worked. Emily emerged from her coma on her seventh birthday and about a week later a CAT scan revealed that her cancer had vanished. This May, Emily celebrated four years of living cancer free.

“That she looks healthy and that people don’t realize what she’s been through, that she can have a normal childhood — that’s what a cure is to me,” said her father, Tom. “I wake up every day happy to see her smiling.”

To date, about 500 patients have received a CAR-T therapy across various company and academic trials, according to David Chang, chief medical officer at Kite Pharma Inc. More than 90 percent of the acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients have gone into complete remission, many of whom had tried three prior types of therapy and failed, according to Marcela Maus, director of cellular immunotherapy at Massachusetts General Hospital’s cancer center. Now the wait is on for more patients to follow Emily toward the five-year survivor mark.

“I would be using the c-word based on what’s available,” Chang said in a telephone interview, without actually ever saying the word “cure” out loud.